Using Jot Form and drop box to collect files.

I have been experimenting with a way to have a remote drop box. Here's a way of using the DropBox service to achieve this. I have set up an account with Jotform. Jot Form will provide a range of ways to link and embed the code. The embed code worked but fails to show the form in Blogger's Preview. It's better to use the iframe code. This one should display in Preview in Blogger.

The last one is as a link to a pop up.

Send a File

There. How useful is that!

OK I have just tested it. The describe field is sent as a separate pdf. A folder is created with the names entered. All are placed in a folder called Jot Form. Impressive. Now I'm going to edit the form. Will it update? YES it does. So the embed is 'live'.

The process seems to mash, at least in the browser, the text's formatting. PDF is the way to go.

Within Drop Box you can share the 'send a file' folder so that just that folder appears on collaborators Drop Box accounts.

Jot Form will permit the sending of zipped folders, multiple files and .movs.

Quite neat.

Wednesday, 23 March 2011

Tuesday, 22 February 2011

Writing outlines -

Take time to map the plot first makes sense.

Take time to map the plot first makes sense. Sometime the easiest route is not the most direct one. When writing scripts the usual approach once you have an idea is to write it out. Starting at the beginning and writing to the end. Last week a number of the students I work with proposed projects that would require some scripting. My advice is always to write an outline first, then write the script. There are excellent examples of writers who don't use this approach. Stephen King is a prime example. In his excellent autobiography ('On writing') he details his writing process. He essentially writes his stories from start to finish. Then there is a reviewing and feedback process. But if you are not a talented writers it's still possible to write a usable script for a short film or media project.

The starting point for this should be an outline. It's often quicker in the long run because you are far less likely to paint yourself into a corner and create an idea you are struck on but can't finish. Otherwise time is wasted trying to fix what never worked while at the same time avoiding re writing the bulk of the script. This only serves to make things HARDER. It's not unusual that there is a time pressure too. You'll feel that it's too late to start again after all the work that already been done.

Writing the outline

You don't need a computer or the internet. Just a sheet of paper, a pen and a little peace and quiet.

1. Write a series of action points listing what we will see in the order that we will see them. Avoid writing dialogue and description, focus on what happens.

2. Where the action moves location organise these points into scenes. List internal or external, the location and the time of day.

3. Add a third line that says what the point of the scene is in relation to the story.

From this simple list you can then start building an idea of:

- the shape or 'structure' - how does the plot develop? Is the story told in the best order?

- whose POV is the story told from? Is this the best one to use to tell the story?

- what might the underlying theme be? Can you develop the theme or topic more?

- is the visual aspect as strong as it can be?

- the audio aspect (sound design) as strong as it can be?

- what is the overall style of the project?

- what is the genre of the project?

- what is the duration of the project?

- what is the scope/scale of the project. Is it too complicated? Can you achieve it satisfactorily?

An outline is easy to share and your creative thinking will benefit as you express your idea to others. They can then either collaborate or feedback on your ideas at an early stage.

Outlines are a good antidote for procrastination! Starting can be hard to do for a range of reasons, not least fear of failing or being disappointed with the end product. Knowing where you're going will add confidence in the eventual outcome.

Outlines make it easier to plan and manage a project and make the deadline.

Sunday, 6 February 2011

Sharing and collaborating materials web 2.1?

For team working Box.net proposes a useful feature.

As web 2.0 moves increasingly into socialising the web it's becoming easier to work on projects with friends, collagues and team mates remotely. Dropbox is a very popular service, (well worth exploring if you haven't already) and it offers a shared folder. This makes it possible to place a file into a shared web based folder, or if the app is installed on the collaborator's computer, onto their hard drive. But there are some additional features that are needed to support comment and communication alongside file sharing.

Box.net

With a recent upgraded version of their service Box.net have some way to answer these issues. Like Drop Box there is a free version as well as a premium service. My comments all relate to the free service. It comes with 5 gigs of storage.

I recently suggested using the service to a team of students who are managing the pre-production on a film project. They have all had to set up accounts and provide an email address. Any of the team can then place/view/download material from the shared folder. Some files can be viewed in directly in the browser. It supports common types of file formats like Word, Excel etc. Each file can have notes and threaded comments attached to it. People can easily be invited to join the 'sharing'. It's also possible to do a group email to all collaborators.

When you log in to your Box.net account you are presented with a list of things that have been updated. However it's not necessary to actually log in to Box.net see what's going on. Each shared folder creates an RSS feed. So all activity can easily be seen using a Feed Reader. I use Google's reader and the excellent 'Reeder' (sic) on the iPhone. (£)

As web 2.0 moves increasingly into socialising the web it's becoming easier to work on projects with friends, collagues and team mates remotely. Dropbox is a very popular service, (well worth exploring if you haven't already) and it offers a shared folder. This makes it possible to place a file into a shared web based folder, or if the app is installed on the collaborator's computer, onto their hard drive. But there are some additional features that are needed to support comment and communication alongside file sharing.

Box.net

With a recent upgraded version of their service Box.net have some way to answer these issues. Like Drop Box there is a free version as well as a premium service. My comments all relate to the free service. It comes with 5 gigs of storage.

I recently suggested using the service to a team of students who are managing the pre-production on a film project. They have all had to set up accounts and provide an email address. Any of the team can then place/view/download material from the shared folder. Some files can be viewed in directly in the browser. It supports common types of file formats like Word, Excel etc. Each file can have notes and threaded comments attached to it. People can easily be invited to join the 'sharing'. It's also possible to do a group email to all collaborators.

When you log in to your Box.net account you are presented with a list of things that have been updated. However it's not necessary to actually log in to Box.net see what's going on. Each shared folder creates an RSS feed. So all activity can easily be seen using a Feed Reader. I use Google's reader and the excellent 'Reeder' (sic) on the iPhone. (£)

Saturday, 5 February 2011

Scheduling tutorials.

Replace paper lists on doors with Typewith.me.

After the recent round of marking comes the inevitable round of feedback tutorials. The usual method for organising this has been a sheet of A4 with a list of possible time slots. Students complete these and turn up at the set times. It's never been a great system since it requires students to visit the tutorial room/office twice. Also there is no easy way for quick swaps and changes to be made amoungst students as their availabilities change.

Last year I used a wiki in Minerva (Blackboard). I allowed all students to edit it and they logged into the VLE, found the module, opened the correct section, selected the wiki page and booked a slot. It worked OK.

This year I have used Typewith.me - a replacement for EtherPad. It creates an openly editable document that can easily be shared by url. There is no login. I set up a page with empty slots. I also embedded the typeWithMe page into Blackboard (See below). I then did a group email with details of the page within Blackboard and a link to the TypeWithMe url outside the VLE. The students completed the booking form quite quickly. I printed it off and used it as a guide for me to the tutorial schedule.

If I were to do this again I would set up several Typewith.me pages with a link from the first to the second, the second to the third etc. These could then be used as the first gets filled etc. Without checking first I knew a series of tutorials was full was when a student emailed me. Otherwise it worked extremely well.

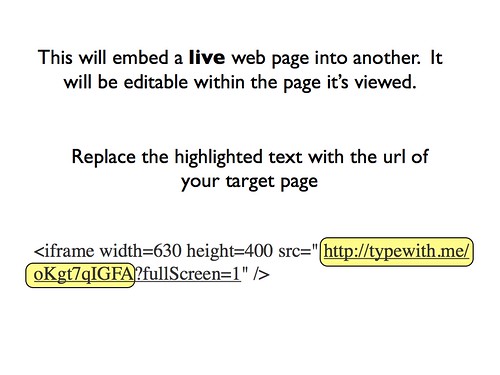

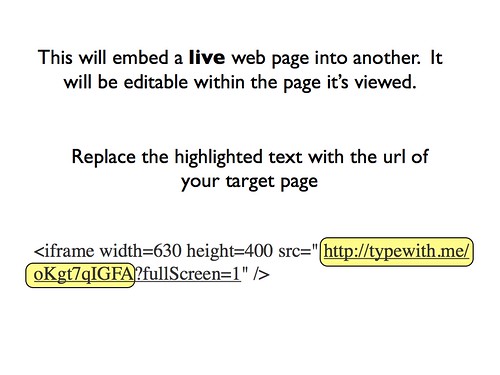

Embedding Typewithme into a Blackboard page.

You need to use the HTML view, but it's not difficult. Copy the url for the Typewith.me page you have created. Open or create a page in Blackboard. With the page in edit mode type something you will spot easily when you switch view to HTML. For example ZOE. Now find ZOE word in HTML view. (On a complicated page I use the find function in Firefox). Over type the word with this code starting with the < bracket to the closing bracket >. Make sure that you paste YOUR url into the section highlighted. Otherwise you will embed the test page. Good Luck.

This is what it should look like - one web page in another. Try it.

After the recent round of marking comes the inevitable round of feedback tutorials. The usual method for organising this has been a sheet of A4 with a list of possible time slots. Students complete these and turn up at the set times. It's never been a great system since it requires students to visit the tutorial room/office twice. Also there is no easy way for quick swaps and changes to be made amoungst students as their availabilities change.

Last year I used a wiki in Minerva (Blackboard). I allowed all students to edit it and they logged into the VLE, found the module, opened the correct section, selected the wiki page and booked a slot. It worked OK.

This year I have used Typewith.me - a replacement for EtherPad. It creates an openly editable document that can easily be shared by url. There is no login. I set up a page with empty slots. I also embedded the typeWithMe page into Blackboard (See below). I then did a group email with details of the page within Blackboard and a link to the TypeWithMe url outside the VLE. The students completed the booking form quite quickly. I printed it off and used it as a guide for me to the tutorial schedule.

If I were to do this again I would set up several Typewith.me pages with a link from the first to the second, the second to the third etc. These could then be used as the first gets filled etc. Without checking first I knew a series of tutorials was full was when a student emailed me. Otherwise it worked extremely well.

Embedding Typewithme into a Blackboard page.

You need to use the HTML view, but it's not difficult. Copy the url for the Typewith.me page you have created. Open or create a page in Blackboard. With the page in edit mode type something you will spot easily when you switch view to HTML. For example ZOE. Now find ZOE word in HTML view. (On a complicated page I use the find function in Firefox). Over type the word with this code starting with the < bracket to the closing bracket >. Make sure that you paste YOUR url into the section highlighted. Otherwise you will embed the test page. Good Luck.

This is what it should look like - one web page in another. Try it.

Saturday, 8 January 2011

Understanding montage and parallel action

This excellent video essay takes 'Inception' and relates it's key storytelling device, parallel editing, to cinema pioneer DW Griffith. But how do Griffith and parallel editing relate to 'montage'?

When one scene follows another again we construct a meaning from their juxtaposition. We have learnt to do this. Similarly when 2 shots are juxtaposed (placed next to each other) we look for a connection or meaning between them. It’s the association of the 2 images that creates meaning for the Viewer. (There can also be a juxtaposition within a single frame too.) We take this so for granted today that as a result it’s sometimes not easy for us to actually decide why some arrangements of images, shots and scenes work better than others. To edit we need to use these ideas since they are the basis of how to assemble a visual story. If we see the shot of a building followed by a woman at a desk we assume that she’s working in the building. This is a learned response developed over time.

The first films of the Lumiere Brothers were single reel, single shot snippets of live or staged action. These would be shown as a collection projected for an audience. George Melies effectively used what we would call ‘in camera’ editing for his theatrical magic shots that showed objects and people disappearing and reappearing. The actual film wasn’t cut and rejoined, he merely cleverly started and stopped the camera.

Until 1902, all scenes were shot in one take from beginning to end. If there was a problem with the take, then the whole thing would be re shot. The audience saw what the film maker had seen, one continuous unbroken piece of action from a single, eye level, all encompassing (wide) view. A direct copy from the theatrical experience. This meant that films were short, 2 − 3 minutes long. Few films were even broken into scenes. But Edison employee, Edwin S. Porter, a resourceful Projectionist, took what he already had - footage of fire companies in action - and combined it with footage he’d filmed, into a single event for ‘The life of an American Fireman’. The juxtaposition suggested that these events were connected and had happened at the same time. By joining separate scenes together his ‘transition’ (a dissolve) released cinema from the constraint of space and ushered in the use of editing as a way of telling the story. The edits served to make the film much more dramatic too. People would now engage more directly with film.

In his next film ‘The Great Train Robbery’ (1903) he cut directly from one scene to another as well as showing simultaneous action by cutting from scene to scene, now know as ‘cross cutting’. People understood that the action shown was happening at the same time. What seems odd to us now is that Porter and others failed to take this technique further and use the cut within the scene. In 1908 he directed DW Griffith in ‘Rescued from the eagle’s nest’. It was Griffith, as a Director, who would take the limelight and cinematic storytelling further that same year.

In spite of his Producers’ concern that the audience ‘wouldn’t pay for half an actor’, in the middle of the action in ‘For love of gold’, Griffith cut from a wide angle to a close up. Importantly the audience understood the cut since it was the same scene from the same camera angle. A year later in ‘After many years’ he cut to a close up of an actress then to the object of her thoughts.

Griffith carried on innovating and for ‘The lonely villa’ (1909) in an attempt to increase the dramatic effect he ‘inter cut’ between the woman and children hiding inside, the bandits outside the villa, and the husband racing home. All the action was within the same scene. Three lines of action were shown, and their screen time bore little relation to real or likely time. All his cinematic storytelling techniques paved the way for longer films - Birth of a Nation and his masterpiece ‘Intolerance’. This film was to have a huge affect on the development of ‘montage’ developed by Russian Directors, most famous of whom was Sergei Eisenstein.

The technique of juxtaposing images has come to be known as ‘montage’, named by Eisenstein from the French meaning ‘assembly’. Montage is used to refer to the associative or intellectual juxtaposition of images. In his quest to deconstruct film-art, theorist Lev Kuleshov’s experiments explored the associative powers of juxtaposition and stressed the role of the editing in their combination.

Lev Kuleshov (http://www.thefullwiki.org/Lev_Kuleshov)

In one experiment Kuleshov used what is now know as the ‘three shot sequence’. He took a piece of film of the actor Muzhukhin with a deadpan expression. He then cut in 3 successive ‘insert’ images; a bowl of soup, a small child and an old woman in a coffin. Then it cut back to Muzhukhin for a ‘reaction’ shot. When viewers saw the cut from Muzhukhin to the insert shot it to be what he was seeing, his POV. The viewers failed to notice that the footage of Muzhukin before and after the insert shot was identical. Instead they were struck by his 'subtle but convincing portrayal' of 3 emotions - hunger for the soup, joy at the child and remorse for the old woman, in the reaction shots. Since there was no acting in the sequences Kuleshov argued that the meaning must have been created in the Viewers’ minds purely by the juxtaposition of uninflected images. By changing the experiment to include different reaction shots he found that the meaning of the sequence could be altered by the shot order. (Smiling - gun - frowning = fear, frowning - gun - smiling = bravery).

Vsevolod Pudovkin (http://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/ruwiki/34522)

Within Soviet Montage there were a number of schools of thought. These were particularly characterised by two ex students of Kuleshov’s; Pudovkin and Eisenstein. Podovkin went on to develop his own ‘5 editing principles’ based on montage theory and juxtaposition:

In 1925 both were charged with making a film about the Revolution. Pudovkin’s family based ‘Mother’ favoured the smooth montage and 'relational editing' of shots that maintained some continuity in time and space, following the route of Griffith.

Mother 1926

While Eisenstein’s grand symphony ‘Potemkin’ favoured more ‘dialectical’ editing, extending the juxtaposition further and abandoning any semblance continuity and providing a shock or jolt. The dialectic is argued using contrast and irony. His ‘collision’ of images used conflictional content, still/dynamic, screen direction, large/small, dark/light, real time/perceived time. He was particularly keen to exploit editing’s ability to create it’s own sense of time, or ‘film time’, drawing out and dramatising particular moments. He also popularised the use of very short shots.

Potemkin 1926

Griffiths, Pudovkin and Eisenstein were all keen on literature and looked to literature to provide them with scenarios and stories (they were particularly keen on Charles Dickens) not so Dziga Vertov. His approach to film and montage was different again…but that’s another story.

‘Temporal ellipsis’ is an editing device that might be confused with montage. In Hollywood and in scriptwriting formatting, this technique is often referred to as a ‘montage’. It is used to compress time, and is visibly seen to do so. It lies in the area between montage and continuity cutting. Filmic time is shortened or speeded up primarily to move the story forward, so unimportant items are omitted - ellipsis.

When one scene follows another again we construct a meaning from their juxtaposition. We have learnt to do this. Similarly when 2 shots are juxtaposed (placed next to each other) we look for a connection or meaning between them. It’s the association of the 2 images that creates meaning for the Viewer. (There can also be a juxtaposition within a single frame too.) We take this so for granted today that as a result it’s sometimes not easy for us to actually decide why some arrangements of images, shots and scenes work better than others. To edit we need to use these ideas since they are the basis of how to assemble a visual story. If we see the shot of a building followed by a woman at a desk we assume that she’s working in the building. This is a learned response developed over time.

The first films of the Lumiere Brothers were single reel, single shot snippets of live or staged action. These would be shown as a collection projected for an audience. George Melies effectively used what we would call ‘in camera’ editing for his theatrical magic shots that showed objects and people disappearing and reappearing. The actual film wasn’t cut and rejoined, he merely cleverly started and stopped the camera.

Until 1902, all scenes were shot in one take from beginning to end. If there was a problem with the take, then the whole thing would be re shot. The audience saw what the film maker had seen, one continuous unbroken piece of action from a single, eye level, all encompassing (wide) view. A direct copy from the theatrical experience. This meant that films were short, 2 − 3 minutes long. Few films were even broken into scenes. But Edison employee, Edwin S. Porter, a resourceful Projectionist, took what he already had - footage of fire companies in action - and combined it with footage he’d filmed, into a single event for ‘The life of an American Fireman’. The juxtaposition suggested that these events were connected and had happened at the same time. By joining separate scenes together his ‘transition’ (a dissolve) released cinema from the constraint of space and ushered in the use of editing as a way of telling the story. The edits served to make the film much more dramatic too. People would now engage more directly with film.

In his next film ‘The Great Train Robbery’ (1903) he cut directly from one scene to another as well as showing simultaneous action by cutting from scene to scene, now know as ‘cross cutting’. People understood that the action shown was happening at the same time. What seems odd to us now is that Porter and others failed to take this technique further and use the cut within the scene. In 1908 he directed DW Griffith in ‘Rescued from the eagle’s nest’. It was Griffith, as a Director, who would take the limelight and cinematic storytelling further that same year.

In spite of his Producers’ concern that the audience ‘wouldn’t pay for half an actor’, in the middle of the action in ‘For love of gold’, Griffith cut from a wide angle to a close up. Importantly the audience understood the cut since it was the same scene from the same camera angle. A year later in ‘After many years’ he cut to a close up of an actress then to the object of her thoughts.

Griffith carried on innovating and for ‘The lonely villa’ (1909) in an attempt to increase the dramatic effect he ‘inter cut’ between the woman and children hiding inside, the bandits outside the villa, and the husband racing home. All the action was within the same scene. Three lines of action were shown, and their screen time bore little relation to real or likely time. All his cinematic storytelling techniques paved the way for longer films - Birth of a Nation and his masterpiece ‘Intolerance’. This film was to have a huge affect on the development of ‘montage’ developed by Russian Directors, most famous of whom was Sergei Eisenstein.

‘All that is best in Soviet film has it’s origins in ‘Intolerance’ Sergei Eisenstein.

The technique of juxtaposing images has come to be known as ‘montage’, named by Eisenstein from the French meaning ‘assembly’. Montage is used to refer to the associative or intellectual juxtaposition of images. In his quest to deconstruct film-art, theorist Lev Kuleshov’s experiments explored the associative powers of juxtaposition and stressed the role of the editing in their combination.

Lev Kuleshov (http://www.thefullwiki.org/Lev_Kuleshov)

In one experiment Kuleshov used what is now know as the ‘three shot sequence’. He took a piece of film of the actor Muzhukhin with a deadpan expression. He then cut in 3 successive ‘insert’ images; a bowl of soup, a small child and an old woman in a coffin. Then it cut back to Muzhukhin for a ‘reaction’ shot. When viewers saw the cut from Muzhukhin to the insert shot it to be what he was seeing, his POV. The viewers failed to notice that the footage of Muzhukin before and after the insert shot was identical. Instead they were struck by his 'subtle but convincing portrayal' of 3 emotions - hunger for the soup, joy at the child and remorse for the old woman, in the reaction shots. Since there was no acting in the sequences Kuleshov argued that the meaning must have been created in the Viewers’ minds purely by the juxtaposition of uninflected images. By changing the experiment to include different reaction shots he found that the meaning of the sequence could be altered by the shot order. (Smiling - gun - frowning = fear, frowning - gun - smiling = bravery).

Vsevolod Pudovkin (http://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/ruwiki/34522)

Within Soviet Montage there were a number of schools of thought. These were particularly characterised by two ex students of Kuleshov’s; Pudovkin and Eisenstein. Podovkin went on to develop his own ‘5 editing principles’ based on montage theory and juxtaposition:

- 1. Contrast

- 2. Parallelism

- 3. Symbolism. Cutting from one shot to a completely different shot that in some way symbolises the action/character in the first

- 4. Simultaneity. This creates tension in the viewer since 2 actions on screen at the same time lead to an outcome that will connect both on screen

- 5. ‘Leit - motif’ - a reinteration of theme. The repetition of shots or a sequence to reinforce the theme

In 1925 both were charged with making a film about the Revolution. Pudovkin’s family based ‘Mother’ favoured the smooth montage and 'relational editing' of shots that maintained some continuity in time and space, following the route of Griffith.

Mother 1926

While Eisenstein’s grand symphony ‘Potemkin’ favoured more ‘dialectical’ editing, extending the juxtaposition further and abandoning any semblance continuity and providing a shock or jolt. The dialectic is argued using contrast and irony. His ‘collision’ of images used conflictional content, still/dynamic, screen direction, large/small, dark/light, real time/perceived time. He was particularly keen to exploit editing’s ability to create it’s own sense of time, or ‘film time’, drawing out and dramatising particular moments. He also popularised the use of very short shots.

Potemkin 1926

Griffiths, Pudovkin and Eisenstein were all keen on literature and looked to literature to provide them with scenarios and stories (they were particularly keen on Charles Dickens) not so Dziga Vertov. His approach to film and montage was different again…but that’s another story.

‘Temporal ellipsis’ is an editing device that might be confused with montage. In Hollywood and in scriptwriting formatting, this technique is often referred to as a ‘montage’. It is used to compress time, and is visibly seen to do so. It lies in the area between montage and continuity cutting. Filmic time is shortened or speeded up primarily to move the story forward, so unimportant items are omitted - ellipsis.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)